SUMMARY

For more than two decades, the net annual increase rate of the installed coal and lignite power worldwide ranged between 20-25GW. However, since 2010, the fuel that has supported the growth of the global economy for decades fell out of favour. This trend is expected to accelerate in the years to come, particularly following the historic agreement of the 2015 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Paris (COP21).

The future of lignite in Greece appears to be even more ominous, given its particularly low quality, the turn of big international finance institutions away from coal, the recent changes in the EU ETS, the tightening up of the European environmental legislation regarding the rest of the air pollutants, as well as the competition with renewables. In the Western Macedonia Region (WMR) in particular, where almost all of the country’s lignite units are located, lignite capacity is expected to decrease by 3,495MW between 2014 and 2030. It’s obvious that the impacts of such developments on the economy of Western Macedonia, which for decades has been relying almost exclusively on lignite, will be dire.

In the midst of these developments, the government and the Public Power Corporation (PPC) seem dedicated to the prolongation of Greece’s lignite-based model for electricity production. They are moving forward with the construction of the new, lignite unit “Ptolemaida V” and also planning to construct a second lignite unit, “Meliti II” in Florina, while PPC has revealed publicly its plans to extensively upgrade the Amyntaio TPS (Thermal Power Station) in order to extend its operation beyond 2023. The lack of institutional initiatives aimed at preparing the transition to a post-lignite era, indicates that the aforementioned actions are considered as the only solution to tackle unemployment in W. Macedonia. This is also illustrated by the fact that a recent request by the five “energy municipalities” of the country, which called for a share of the revenue generated by auctioning of CO2 allowances to be used to create jobs in the three “lignite Regional Units” of Greece, was rejected.

At a first stage, the present study examined the local added value and the jobs that will be lost as a result of the expected shut-down of lignite units in W. Macedonia over the next 15 years (“Inaction Scenario”). It then examined the extent at which constructing new lignite units can make up for this loss. The results of the economic assessment were negative:

Ptolemaida V and Meliti II can reinstate only 30% of the jobs and the local income that inevitably will be lost, despite the fact that their construction will require investments in the order of €2.5 billion. It is therefore necessary to investigate the potential that alternative sectors of the economy have in tackling this issue.

For this purpose, a preliminary plan for WMR’s transition to a post-lignite era was developed and the corresponding investment cost was estimated, elaborating on past proposals by stakeholders in Western Macedonia. In this context, three scenarios were formulated, assuming a “mild”, “medium” and “strong” development respectively, each focusing on economic activities that are not related to lignite extraction and burning and whose implementation can be carried out over a 15-year period. More specifically, emphasis in the primary sector was placed on the cultivation of Kozani saffron and aromatic and energy plants, along with the further development of the forestry sector. In the secondary sector, the fundamental pillar was the development of Renewable Energy Sources, energy savings, waste management, the operation of a fly ash processing facility, and the processing of aromatic plants. Finally, the tertiary sector relies on the development of tourism, with an emphasis on industrial tourism and ecotourism, as well as on carrying out research in academic institutions and research centres in Western Macedonia.

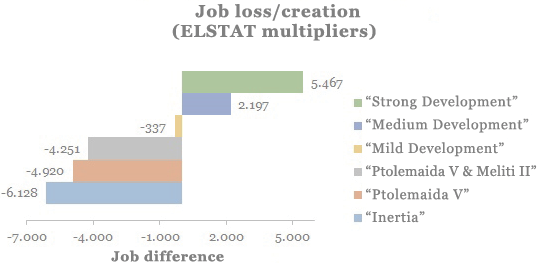

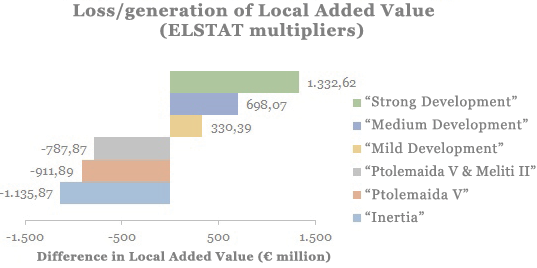

In order to estimate the multifold effects that the implementation of these scenarios will have on Western Macedonia’s economy as a whole, input-output analysis at a regional level was used, regarding both job opportunities and local added value (LAV). For comparison purposes two different groups of regional multipliers were used: those based on Hellenic Statistical Authority (ELSTAT) data for 2011, and those based on a study by the Academy of Athens/Technical Chamber of Greece-Western Macedonia department (TCG-WM) which, however, uses older data (dating back to 2001 and 2005 for employment and added value respectively) and different economic sectors compared with ELSTAT’s. The results of the analysis using the newer multipliers – based on ELSTAT’s figures – are summarised in the following graph.

Comparison of 6 scenarios regarding the job opportunities and the Local Added Value they create compared with the “Inaction” scenario (ELSTAT multipliers)

Even in the “mild” development scenario, which was based on particularly modest assumptions, almost the same number of jobs and a higher LAV as those that will be lost from shutting down the lignite Thermal Power Stations (“Inaction scenario”) can be created. Significant improvement can be achieved in the “medium” development scenario, as based on ELSTAT’s multipliers, there will be 2,197 more jobs created compared with those that will be lost by shutting down the lignite stations by 2030, while LAV is estimated at €1.834 billion, approximately €0.7 billion higher than that of the “inaction” scenario.

Even in the “mild” development scenario, which was based on particularly modest assumptions, almost the same number of jobs and a higher LAV as those that will be lost from shutting down the lignite Thermal Power Stations (“Inaction scenario”) can be created. Significant improvement can be achieved in the “medium” development scenario, as based on ELSTAT’s multipliers, there will be 2,197 more jobs created compared with those that will be lost by shutting down the lignite stations by 2030, while LAV is estimated at €1.834 billion, approximately €0.7 billion higher than that of the “inaction” scenario.

The “strong” development scenario presents the greater benefits to the economy of WMR. Using ELSTAT’s multipliers, almost twice the number of jobs and more than twice the LAV can be created compared with those lost (“Inaction scenario”).

ENG

ENG

BUL

BUL

GER

GER

POL

POL

GR

GR